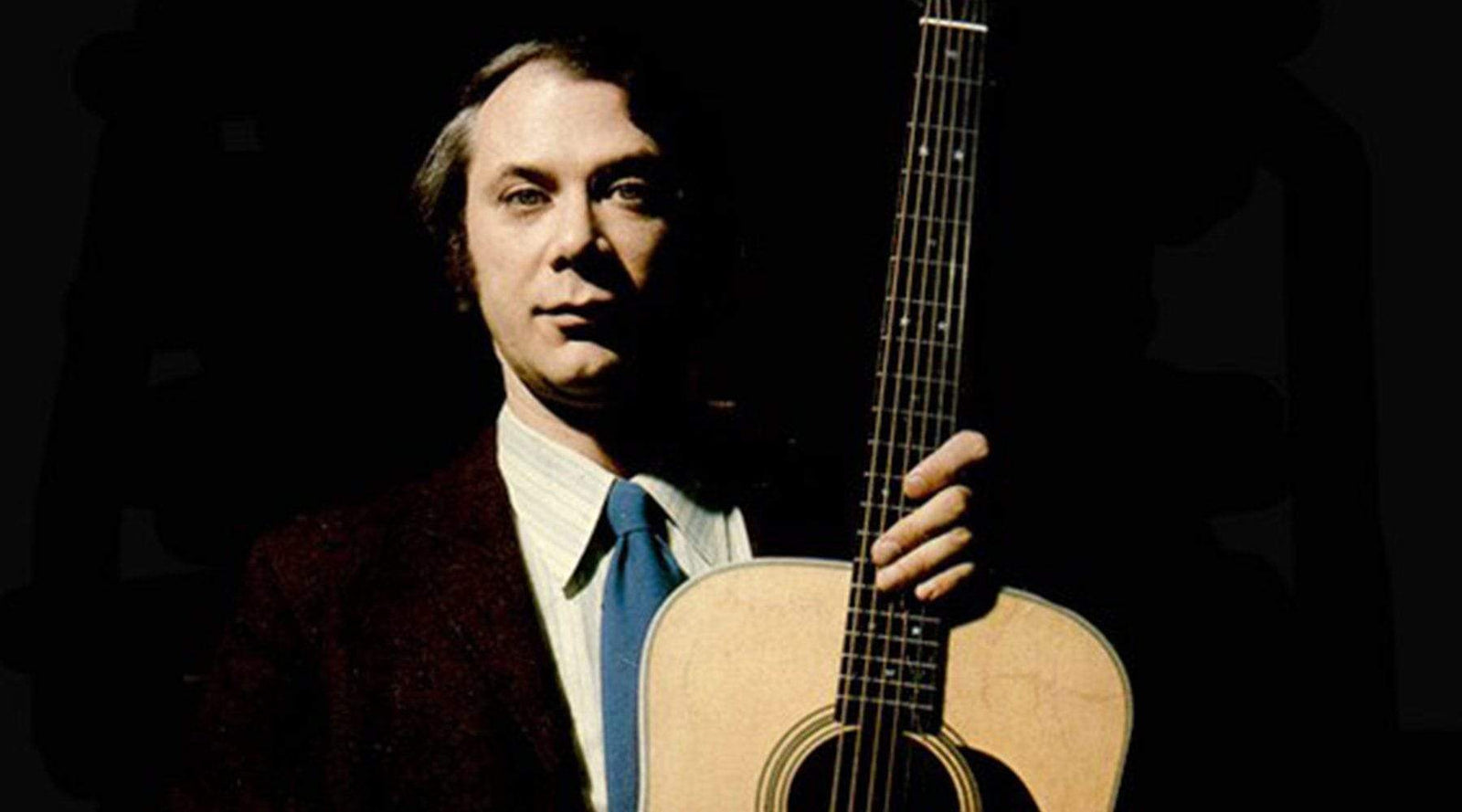

The Genius of John Fahey

"It's hard to imagine what contemporary music would be like if people like John Fahey had not been obsessively fascinated with roots American music from the 1920s and 30s. That's the secret of a whole swathe of modern rock'n'roll.”

- Rob Bowman, Musicologist

There are plenty of influential fingerstyle guitarists out there. But, few can lay claim to pioneering a new genre.

There are plenty of influential fingerstyle guitarists out there. But, few can lay claim to pioneering a new genre.

John Fahey has that distinct honor. Credited with originating American primitive guitar pretty much single handedly in the 1950s and 1960s, he’s one of the great pioneers of American blues and folk music. Yet, outside of a small, but passionate community of enthusiasts, he remains something of an unknown quantity.

Today, we’re shedding some light on the genius of John Fahey, his music, and why more people should be aware of his impact on folk music and beyond.

Born on in Washington D.C., on February 28th 1939, Fahey spent his formative years surrounded by music. Both his mother and father were piano players and country and bluegrass enthusiasts. But, it wasn’t until he heard Bill Monroe singing “Blue Yodel No. 7” on the radio that Fahey was inspired to become a musician himself.

Born on in Washington D.C., on February 28th 1939, Fahey spent his formative years surrounded by music. Both his mother and father were piano players and country and bluegrass enthusiasts. But, it wasn’t until he heard Bill Monroe singing “Blue Yodel No. 7” on the radio that Fahey was inspired to become a musician himself.

His first guitar was purchased for $17 from the Sears, Roebuck catalogue in 1952, and an interest in record collecting soon followed. Like his parents, he was a fan of bluegrass and country. Hearing Blind Willie Johnson’s “Praise God I’m Satisfied” on a record-collecting trip to Baltimore, he also became a convert to early blues music. And convert is the apt term – Fahey once recalled that hearing Johnson for the first time was like being "smote to the ground by a bolt of lightning."

But Fahey, while transformed by the likes of Johnson and Skip James, was no blues purist. He was also passionate about contemporary classical composers such as Charles Ives and Béla Bartók. And his playing style blended these two influences in an unconventional way; his compositions combined the dissonance of contemporary classical with the traditional blues fingerpicking patterns he was hearing on old ’78 records.

But Fahey, while transformed by the likes of Johnson and Skip James, was no blues purist. He was also passionate about contemporary classical composers such as Charles Ives and Béla Bartók. And his playing style blended these two influences in an unconventional way; his compositions combined the dissonance of contemporary classical with the traditional blues fingerpicking patterns he was hearing on old ’78 records.

In 1959, his first record – “Blind Joe Death” – was self-released under his own Tahoma records imprint. He had no idea how to approach record companies at this time, so pressed 100 copies of the album, in part with funds he raised as a gas station attendant.

In 1959, his first record – “Blind Joe Death” – was self-released under his own Tahoma records imprint. He had no idea how to approach record companies at this time, so pressed 100 copies of the album, in part with funds he raised as a gas station attendant.

The first side of the record was credited to Fahey himself, the second to a fictional bluesman whose name was the album’s title. Fahey would later note of his alter-ego, who was to become an important figure in his own legend:

"…the whole point was to use the word 'death'." Blind Joe Death was my death instinct. He was also all the Negroes in the slums who were suffering. He was the incarnation, not only of my death wish, but of all the aggressive instincts in me."

Moving to Berkley in 1963 to study philosophy at the University of California, Fahey found himself disaffected with the post-Beat, proto-hippie music scene. In particular, it was the Pete Seeger-inspired revivalists that irked the iconoclastic guitarist. This frustration was reflected in his records released on the growing Tahoma label during the mid-1960s, as well as Vanguard records, which also started issuing his music.

Skip James-inspired blues clashed with Georgian chanting and chords lifted from Vaughan Williams symphonies. Sound collages of Gamelan music, Tibetan chanting and animal cries interspersed his guitar playing. In the lengthy, and wordy liner notes that accompanied these releases, he parodied the pretentiousness of the blues purists. In 1965, he resurrected Blind Joe Death for “The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death” album, which many regard as his seminal work. By this time, Joe had a backstory, a guitar made out of a baby’s coffin and was the one who taught Fahey to play; details designed to further wind-up the authenticity-obsessed blues fans of the era.

Skip James-inspired blues clashed with Georgian chanting and chords lifted from Vaughan Williams symphonies. Sound collages of Gamelan music, Tibetan chanting and animal cries interspersed his guitar playing. In the lengthy, and wordy liner notes that accompanied these releases, he parodied the pretentiousness of the blues purists. In 1965, he resurrected Blind Joe Death for “The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death” album, which many regard as his seminal work. By this time, Joe had a backstory, a guitar made out of a baby’s coffin and was the one who taught Fahey to play; details designed to further wind-up the authenticity-obsessed blues fans of the era.

It was this iconoclastic and experimental streak that made Fahey so difficult to categorize, and is perhaps part of the reason for his lack of mainstream recognition. As biographer Steve Lowenthal notes:

“It’s always tricky to pin Fahey down, as he was very much a contrarian and his thoughts reflected his moods, which fluctuated. Fahey always wanted to be a composer. In fact, he wished his Vanguard LPs were released in the classical series rather than the folk catalog. That being said, Fahey lacked the discipline or skill to learn to read and write music, insuring his exclusion from that particular canon.”

In the late-1960s music scene however, where “do your own thing” was very much the modus operandi, Fahey found favour. Takoma records grew from strength to strength, spawning kindred spirit American primitivists like Leo Kottke, Bob Hadley and Peter Lang.

In the late-1960s music scene however, where “do your own thing” was very much the modus operandi, Fahey found favour. Takoma records grew from strength to strength, spawning kindred spirit American primitivists like Leo Kottke, Bob Hadley and Peter Lang.

Yet, as the decade turned, so did Fahey’s fortunes. His health deteriorated, exacerbated by a growing drinking problem. He lost his home, and went through multiple divorces. In 1979, Takoma was sold to Chrysalis records. Then, in 1986, he contracted Epstein-Barr syndrome. He beat the condition five years later, but was left impoverished as a result. By the early 1990s, he was living in and out of cheap motels, pawning guitars and reselling rare records to make rent. When the album “Old Girlfriends and Other Horrible Memories” was released in 1992, those few devotees still following Fahey’s career assumed it would be his last.

Fahey, however, was due one last revival, spearheaded by a 1994 entry in Spin Magazine’s Alternative Record Guide. Alternative bands like Sonic Youth and Cul de Sac were singing his praises. A lengthy feature in Spin – “The Persecutions and Resurrections of Blind Joe Death” – brought his music to a new generation.

Fahey, however, was due one last revival, spearheaded by a 1994 entry in Spin Magazine’s Alternative Record Guide. Alternative bands like Sonic Youth and Cul de Sac were singing his praises. A lengthy feature in Spin – “The Persecutions and Resurrections of Blind Joe Death” – brought his music to a new generation.

A two-CD retrospective – “The Return of the Repressed” (it’s probably still the definitive Fahey compilation) – was released to capitalize on this interest. A slew of new albums followed in rapid succession, along with reissues of his Tahoma output from the 1960s and 1970s. In 1997, he was awarded a Grammy for his contributions to the liner notes of Revenant Records’ “Anthology of American Folk” series.

But, while recognition for Fahey grew, his financial problems and health issues continued. Still living out of motel rooms well into the 1990s, he passed away in 2001 – just two days shy of his 62nd birthday – after undergoing a sextuple coronary bypass operation.

Unconventional, iconoclastic, and always inventive, Fahey’s playing showed shades of the folk, blues and gospel that influenced it, yet managed to sound like nothing you’d ever heard before. At times irreverent and acerbic, his music nonetheless had a compelling, introspective quality that captivates the listener and doesn’t let go. Or, as Sean O’ Hagan put it in the Guardian: “it seems to evoke the entire history of popular music, and yet suggest some place beyond it, a place both real and mythical, timeless and resonant.”

Unconventional, iconoclastic, and always inventive, Fahey’s playing showed shades of the folk, blues and gospel that influenced it, yet managed to sound like nothing you’d ever heard before. At times irreverent and acerbic, his music nonetheless had a compelling, introspective quality that captivates the listener and doesn’t let go. Or, as Sean O’ Hagan put it in the Guardian: “it seems to evoke the entire history of popular music, and yet suggest some place beyond it, a place both real and mythical, timeless and resonant.”

So here’s to the unsung genius of John Fahey; a pioneer, a primitive, and a monumental figure in American blues and folk.